|

Report from

Europe

Record low EU27 tropical timber imports in 2020

Total EU27 (i.e. excluding the UK) import value of

tropical wood and wood furniture products was US$2.99

billion in 2020, 9% less than the previous year.

This is a significantly higher level of import than forecast

when the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the

continent early in 2020. It was, however, the lowest level

in recent decades and represented a further decline in a

market which has been severely restricted ever since the

financial crises (Chart 1).

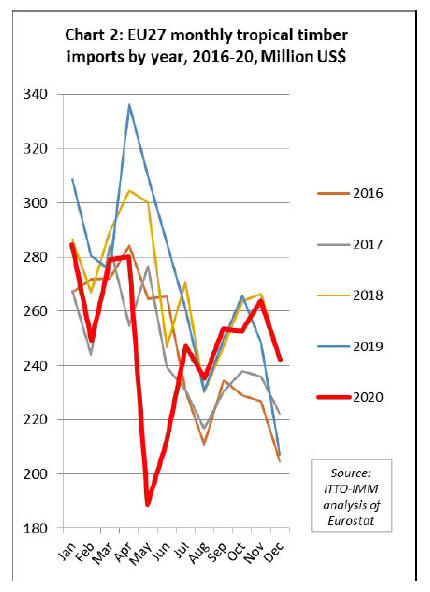

Total EU27 tropical wood and wood furniture import

value in December 2020 was US$242 million, an 8% fall

compared to the previous month. However imports during

December were relatively high for that month, being 17%

more than the same month in 2019, as products continued

to arrive after delays earlier in the year (Chart 2).

Consumption was holding up much better than expected

across many sectors, from construction and DIY to

merchants and furniture makers.

In fact material supply has been more of an issue than

demand, particularly due to lack of container space and

soaring freight rates. With global container distribution

disrupted by the pandemic, shippers out of Asia have been

naming their price. Importers report five- and six-fold rises

in container rates since mid-2020.

Decline in EU27 imports recorded for all tropical wood

product groups

Unsurprisingly, EU27 imports of all the main tropical

wood products fell in 2020, but in each case the decline

was less dramatic than expected earlier in the year when

the scale of the pandemic and associated lockdown

measures was just becoming apparent. Further analysis of

EU imports will be provided in the end April report.

Discussion on possible merger of EUTR with EU

deforestation©\free regulations

The EU is considering introduction of new forest and

climate policy measures which would reshape timber trade

relations with tropical countries. In some ways, the

proposed measures build on the existing policy framework

contained in the FLEGT Action Plan. However, they also

raise questions about the future of existing instruments

such as the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) and FLEGT

licensing systems.

The potential far-reaching implications of the on-going

policy discussions were highlighted in a presentation by

Hugo Schally of the European Commission¡¯s

Environmental Directorate (EC DG ENV) to a webinar

hosted by FERN, the Brussels based environmental NGO,

on 17 March 2021 which brought together a range of

policy makers and civil society stakeholders for

presentations and discussions on the theme ¡°Enforcing

Due Diligence regulation for forest risk commodities.

See:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zuaEQggFXCE

Mr. Schally starts speaking at around 1hr 15 minutes into

the webinar

Mr. Schally¡¯s presentation provides an insight into the

EC¡¯s latest thinking on international forestry-related issues

at a time when the EU has committed - referenced in three

separate policy instruments; the European Green Deal, the

EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Farm to Fork

Strategy - to present, in 2021, a legislative proposal to

avoid or minimize the placing of products associated with

deforestation or forest degradation on the EU market.

This commitment follows the 2019 EU Communication on

¡°Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the

World¡¯s Forests¡±. It was also reinforced in October last

year when the European Parliament adopted MEP Delara

Burckhardt¡¯s report, ¡®An EU legal framework to halt and

reverse EU-driven global deforestation¡¯.

Burckhardt¡¯s report calls on the Commission to ensure

companies are obligated to conduct due diligence on

deforestation and human rights before placing ¡°forest risk¡±

goods on the EU market. It also suggests financial

institutions conduct due diligence before providing money

to companies that harvest, extract, produce, process or

trade forest- and ecosystem-risk commodities and derived

products. It further calls for traceability obligations to be

placed on EU market traders of these products.

The European Parliament¡¯s decision pre-empted the EC¡¯s

on-going impact assessment of regulatory options to

¡°decrease the risk of imported deforestation and forest

degradation¡±. The impact assessment, the results of which

have yet to be published, is being undertaken by EC DG

ENV drawing on insights from a public consultation held

in the last quarter of 2020.

This impact assessment will also take account of the

results of the on-going Fitness Check, also led by EC DG

ENV, of the FLEGT and EUTR regulations, the two key

legal instruments of the EU FLEGT Action Plan.

Supported by a public consultation undertaken early last

year and an external study (not yet published), the fitness

check is looking at the effectiveness, efficiency,

coherence, relevance and EU added value of both

regulations in contributing to the fight against illegal

logging globally.

Presenting to the FERN webinar under the heading ¡°EU

Action on Deforestation: State of Play¡±, Mr. Schally

began by explaining some of the EU thinking behind a

new regulatory approach focused on agricultural

commodities in addition to timber products, implying this

gave greater market leverage.

¡°[The FLEGT and EUTR regulations] have to be seen in

the policy context of the early 2000s¡and the way the

problem was seen at that point in time, namely that the

major driver and the main problem was identified as

commercial logging, and therefore the focus was on timber

trade¡±.

¡°And, of course, when we did the impact assessment on

the new timber regulation, it was clear that international

trade in timber and derived products, was when you look

at overall sizes of the markets and of the economies, was a

fairly marginal issue economically.¡ when you talk about

the proposal that is in the making [for due diligence

regulation], this is radically different, it deals with a broad

range of agricultural commodities, I think we go into a

different ballpark figure¡±.

As background to this new regulation, Mr. Schally

mentioned some of the EC¡¯s preliminary conclusions from

their on-going Fitness Check of the EUTR, noting both

positive results and continuing challenges, particularly for

smaller operators.

¡°Now I think that we all agree that when the results of the

fitness test will be handed out that there has been a

positive result with regard to incentivizing companies to

keeping supply chains clear, however, we have come

across a number of major challenges which is that

infractions under the EUTR are difficult to prove and

substantiate in court, which undermines its dissuasive

power¡±.

¡°And I think that one main complaint that the member

states¡¯ competent authorities have is we're dealing with

complex supply chains with a lot of small and medium

sized enterprises, which leads to high costs for companies,

perhaps too high in that regard (we're still checking on

that), that when you look at the situation over the years,

the imports of timber from some high risk countries where

we can be fairly sure that there is a good proportion of

illegal timber involved has actually increased.

Mr. Schally also elaborated on some specific challenges of

legal interpretation that makes prosecution difficult in the

EUTR, ¡°The term negligible or non-negligible risk is

subjective. The legal system in the member states, very

often have no clear understanding and no long standing

tradition in dealing with the concept of due

diligence¡..We have seen some member states where this

has almost paralysed prosecution and enforcement and

made it really hard to apply any sanctions to governments

in question¡±.

Moving on to FLEGT regulation, Mr. Schally questioned

the value of the legality licensing approach which has been

a core component of the VPA process to date.

¡°Now, on the FLEGT regulation, I think that we need to

make the distinction of what has worked and what hasn't

worked, and I think that the positive story of the FLEGT

VPAs, is that where we have VPA processes we see

positive results in terms of enhanced stakeholder

participation in policymaking and the national level

improvements in forest governance and administration and

some enforcement.

¡°However, when we look at it - and I think it's not

surprising because we're dealing with illegal logging -

there is no hard evidence that VPAs have contributed to

reducing illegal logging in partner countries, or the

consumption of illegally harvested wood in the EU.

¡°That's partially due to the fact that since 2005 when we

started with that regulation, only one country out of the 15

with whom we have engaged has an operating licencing

system in place. And when you look at the overall trade

pattern, only one VPA country is among the top 10 EU

trading partners, which is Indonesia again.

¡°So I think that from our perspective, the part where we

are not confident has made its proof is the licencing

system, and the timber legality assurance system in partner

countries¡±.

While questioning the specific role of legality licensing,

Mr. Schally did, however, emphasise the continuing value

of partnership agreements: ¡°But I think that one thing that

we absolutely need under all costs to be maintained, is the

support mechanism to enable partner countries to comply

with requirements without the elements that do not work.¡±

But he also stressed that the EU¡¯s intent will be to change

the scope and focus of these agreements, to include a

wider range of forest-risk commodities, mentioning beef,

palm oil, soy, rubber, cereals, cocoa, and coffee alongside

wood. He suggested that ¡°it's very clear we're moving

from legality to sustainability¡± and that ¡°there would not

be added value in a dual system for legality on the one

hand and sustainability on the other hand¡±.

Rather than focusing on illegal logging, Mr. Schally said

¡°it is clear that we need to deal with agricultural

production and agricultural expansion, and we actually

need to move from a system that rewards effort and

announcement to a system that rewards performance and

effect.¡±

Moving on to consider the legislative instrument to be

introduced in the EU, Mr. Schally noted four specific

objectives:

¡°to minimise the risk of placing on the EU market

commodities associated with deforestation and

forest degradation;

to make sure EU consumers and citizens are

aware of the impact; thereby,

to promote the demand for and consumption of

commodities and products that are not associated

with deforestation and forest degradation;

and

to incentivise investment and financial interest in

sustainable production systems¡±.

Mr. Schally identified ¡°one of the cornerstones¡± of the

new initiative as the ¡°deforestation free criteria, including

forest degradation¡±, which he said ¡°needs to be based on

solid science¡±. He referenced various relevant sources

including the FAO definition of deforestation, the

UNFCCC and REDD+, and High Carbon Stock Approach.

He suggested that under the new proposed legislation

products from plantations would still be allowed to be

placed on the EU market, but this may be subject to a cutoff

date for conversion yet to be determined, mentioning

that the European Parliament report said this should be no

later than 2015.

In relation to the specific obligations placed on wood and

agricultural commodity traders, and despite having

highlighted some of the challenges of the EUTR due

diligence approach, Mr. Schally noted that ¡°in the end, a

variety of due diligence is what works best because with

all stakeholders, we can actually build on experiences that

they have had with implementing due diligence

requirements¡±.

However, he also suggested mechanisms be introduced to

ensure due diligence does not overburden competent

authorities and economic operators. ¡°We really feel that

[due diligence] needs to be complemented by some

benchmarking country assessments, possibly also by a

system by which public certification systems in third

countries and EU member states would be recognised.

¡°That would mean we would arrive at a tiered system of

due diligence with more requirements for some and less

requirements for others, depending on the fact whether

there is mandatory public certification or benchmarking¡±.

Mr. Schally suggested, however, that a specific

¡°deforestation free requirement¡± for forest-risk

commodities placed on the EU market would be a ¡°nuclear

option¡± and likely very challenging to implement ¡°because

that's a very linear application of the EUTR system to

trade in agricultural commodities¡±. He concluded, ¡°we're

still assessing [the deforestation-free requirement] but I

think that probably whatever we do an element of due

diligence will be important¡±.

While Mr. Schally¡¯s comments are preliminary and views

may alter before any official EU policy is announced,

some of the observations relating to the perceived lack of

effectiveness of the EUTR and FLEGT licensing system in

removing illegal wood from EU trade imply that the EC is

considering a significant change in policy direction.

At this stage it is impossible to foresee the impacts of such

a change in policy direction; however it is possible that

EUTR may be rolled into the broader regulation covering

all ¡°forest risk¡± commodities and including deforestation

free requirements. As for the VPAs, after a period of 15

years when the EU has been actively encouraging tropical

countries to adopt FLEGT licensing systems for timber

products through these legally binding trade agreements,

the focus of future negotiations may change significantly.

The objective may be to finalise agreements covering all

¡°forest risk¡± commodities, as defined in the new EU

regulation, and to develop procedures for ¡°benchmarking

country assessments¡± and ¡°public certification¡± to

demonstrate that their trade does not to contribute to

deforestation or forest degradation.

There may also be a greater emphasis in the agreements on

monitoring the impacts of agricultural commodity trade on

forest carbon stocks.

This would align with another anticipated EC policy

measure, to introduce a border carbon levy for which a

detailed proposal is expected in June. This levy is

expected to help finance NextGenerationEU, the €750

billion ($888 billion) economic recovery instrument now

being rolled out across the EU while also contributing to

the EU target of cutting emissions by 55% compared to

1990 levels by 2030 on the way to making the EU climate

neutral by 2050.

Mr. Schally¡¯s comments on the limitations of EUTR and

FLEGT licensing raise immediate questions about the

future of the EU¡¯s existing FLEGT VPAs ratified with

seven tropical timber producing countries ¨C Cameroon,

Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Ghana,

Indonesia, Liberia, and Viet Nam ¨C plus the two

agreements still awaiting ratification with Guyana and

Honduras.

The stakes are particularly high for Indonesia which has

been issuing FLEGT licenses now for nearly five years

and has successfully applied its timber legality assurance

system (TLAS) and SVLK certification to all wood

product exports and is looking to the EU to follow up on

specific commitments made in the VPA ¡°to promote a

favourable position in the Union market¡± for FLEGT

licensed products, including specific ¡°efforts to support:

(a) public and private procurement policies that recognise

a supply of and ensure a market for legally harvested

timber products; and (b) a more favourable perception of

FLEGT-licensed products on the Union market¡±.

This implies continued commitment to the ¡°green lane¡±

for FLEGT licensed products in the EUTR, which at least

before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was

beginning to pay dividends in terms of rising market share

for Indonesian wood products in the EU. It also implies

further efforts to communicate the benefits of FLEGT

licensing, of the sort described in the 2020 report by the

Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)

¡°Collecting Evidence of FLEGT-VPA Impacts for

Improved FLEGT Communication¡±.

The CIFOR report, which draws on research in Cameroon,

Ghana and Indonesia, concludes that ¡°globally, the VPA

process has contributed positively towards a decrease in

illegal logging rates particularly illegal industrial timber in

export markets, notably derived from production forests

being mandated to have management plans.

¡°At the country-level this held true across Cameroon,

Ghana, and Indonesia as the share of legal timber in export

markets had gone up with direct attribution to VPAs. In

Indonesia, the share of national timber production

exploited with a legally obtained permit has also gone up.

Further, across each country, the ultimate goal of SFM

was being better achieved through more thorough

implementation of forest management plans¡±.

CIFOR stressed that ¡°the VPA process has contributed

positively to a more coherent legal and regulatory

framework with sanctions being more regularly enforced

and more credible due to the VPA, and to greater

transparency in the forestry sector¡±.

Following on from Mr. Schally¡¯s comments, and a similar

presentation delivered by the EC on 25 February to the

¡°Multi-stakeholder platform with a focus on Deforestation

and Degradation¡±, an invitation-only group of mainly

European trade associations and NGOs, a joint response

was issued by Indonesia¡¯s Civil Society Organization

(CSO) Coalition working in monitoring the

implementation of TLAS-SVLK.

Slides of the presentations of this meeting are available at :

https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupMeeting&meetingId=23741

The Indonesian CSOs state that ¡°Without clearly

understanding the research method applied to obtain the

data, whether the data source has been validated and to

what extent the partner countries were consulted, the

stakeholders felt that the European Commission was too

early in concluding that the VPAs have not contributed to

reducing illegal logging in partner countries and did not

capture other detailed information related to the impact of

FLEGT VPA¡±.

The statement highlights that ¡°since the implementation of

SVLK, the number of illegal logging cases declined from

nearly 1800 cases in 2006 to 80 cases in 2020¡± and ¡°since

the implementation of FLEGT licence in 2016,

Indonesia¡¯s timber product export value increased from

USD 9.84 billion in 2016 to USD 11.05 billion in 2020.

Meanwhile, furniture export in 2019 rose 14.5% and in

2020 (during the Covid-19 pandemic) continued to

increase by 12.2% (USD 2.18 billion)¡±.

¡°Furthermore that during VPA implementation, legal

timber and timber products administrative system

(logging, distribution, processing, trade) in Indonesia

experienced an improvement, which reduced the space for

illegal logging and timber distribution. In the wood chip

processing industry, SVLK implementation had a positive

impact on reducing indications of illegal timber entering

the supply chain¡±.

Finally the Indonesian CSO statement ¡°underlined the

issue of market uptake, in which the EU has not fully

support[ed] and promote[d] FLEGT-licenced timber from

Indonesia, as mandated in the VPA text.¡±

|