|

Report from

Europe

Asian wooden furniture manufacturers losing share in

European market

There was a robust rebound in EU wooden furniture

production and trade in 2014 and 2015. As noted in earlier

ITTO reports, wooden furniture production value in the

EU (excluding kitchen furniture) was euro 31.15 billion in

2015, 4.4% more than 2014 and nearly 9% up on 2013,

with gains made in all the main EU manufacturing

countries

EU imports of wooden furniture from outside the EU were

worth euro 5.73 billion in 2015, 13% more than the

previous year and 25% up on 2013. EU exports of wooden

furniture rose to euro 8.73 billion in 2015, up 3.5% from

2014 and 6% more than in 2009

While no EU furniture production data for 2016 has yet

been published, early signs are that production has

continued to rise this year even while external trade with

non-EU countries has declined. In other words, European

manufacturers are taking a larger share of the internal EU

market in 2016, squeezing out overseas competitors at

home as their efforts to expand sales to non-EU countries

are beginning stall.

Eurostat data shows that the value of wooden furniture

exports by EU countries to other countries within the EU

was euro 8.16 billion in the first half of 2016, 7.3% more

than the same period in 2015. In contrast, the value of

exports to countries outside the EU declined 1% to euro

4.16 billion in the first half of 2016.

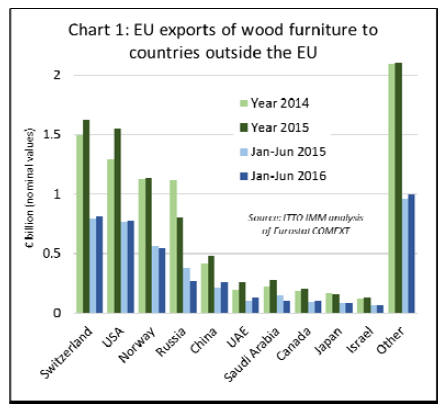

The slowdown in EU exports this year is mainly due to a

30% decline in exports to Russia. EU exports to other

countries continue to rise (Chart 1).

Meanwhile external suppliers of wood furniture,

particularly in the tropics, seem to be struggling in what

has become an extremely competitive market. The EU

imported wooden furniture with a total value of euro 2.97

billion in the first six months of 2016, 2% less than the

same period in 2015.

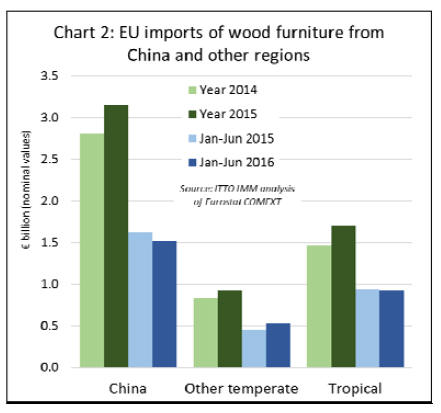

After making significant gains in the EU market in 2015,

EU wooden furniture imports from China and tropical

countries have slipped back this year. In the first six

months of 2016, import value from China declined 7% to

euro 1.51 billion and import value from tropical countries

declined 1% to euro 930 million.

However, EU import value from non-EU temperate

countries increased by 16% to euro 528 million, with

particularly large gains by Turkey, Bosnia and Serbia

(Chart 2).

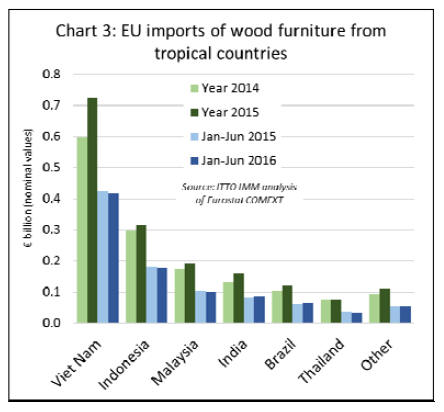

EU import value of wooden furniture declined from all of

the largest South East Asian suppliers in the first six

months of 2016.

The value of EU import from Vietnan declined by 1.5% to

euro 416 million, by 3.1% from Indonesia to euro 176

million, by 5.2% from Malaysia to euro 100 million, and

by 8.8% from Thailand to euro 34 million.

However, there were gains in imports from India (+7% to

euro87 million) and Brazil (+7% to euro 63 million).

(Chart 3).

Overall, the signs are that, unlike in North America,

domestic manufacturers are maintaining and even

extending their domination of the European wooden

furniture market.

There are many reasons for this. An obvious short term

factor is weakening of European currencies in the last 2

years 每 particularly the UK pound since Brexit - against

the dollar and Chinese yuan.

More enduring factors include: the relative high degree of

fragmentation in the European retailing sector 每 which

greatly complicates market access for overseas suppliers;

the underlying strength of European furniture

manufacturers and their brands in terms of innovation and

design; the obstacles to overseas suppliers complying with

complex EU technical and environmental standards; and

the expansion of furniture manufacturing in Eastern

Europe, a location which combines ready access to raw

materials, relatively cheap labour, and the internal EU

market.

While it seems likely that domestic manufacturers will

continue to dominate Europe*s wooden furniture market in

the years ahead, there are significant changes underway

which are altering the terms of trade. While some changes

are likely to create new obstacles for external suppliers,

others may provide opportunities.

Two factors are particularly significant and explored in the

following sections: the decision of the UK to leave the EU,

so-called Brexit; and the strategy of IKEA, already a

dominant force in the European market place, to increase

their market share through a strategic focus on

※sustainability§ and all that implies for product design,

material procurement, energy efficiency and waste

management.

Brexit: far-reaching consequences for EU wooden

furniture market

Brexit is particularly significant for the wooden furniture

sector as the UK is the largest single EU destination for

this commodity imported from outside the EU. In 2015,

the UK accounted for 36% of all EU imports of wooden

furniture from outside the single market.

This is due to the relatively high degree of consolidation in

the UK*s furniture retailing sector compared to other EU

countries, and the UK*s relatively high level of openness

to foreign trade and products, comparatively small

domestic furniture sector, and longer distances from the

heartland of EU furniture manufacturing in Italy, Germany

and Poland.

Fears of economic fallout from Brexit have led to an

immediate and large devaluation of the British pound

against other currencies. Throughout October, the pound

has been trading at around US$1.22 against the dollar, the

lowest level for 31 years and 18% less than just before the

Brexit vote.

At times during the month the pound also dropped below

the psychologically important euro 1.10 level against the

euro, its lowest level since March 2010 and 15% less than

before the vote.

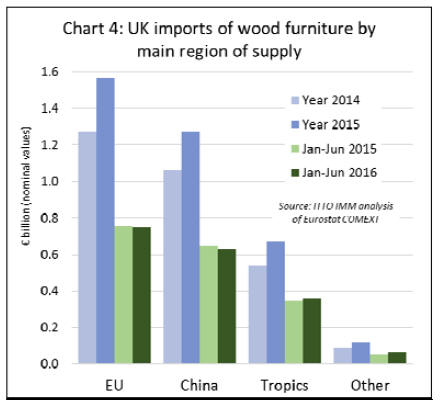

After a year of strong growth in 2015, the UK*s imports of

wooden furniture had levelled off at the higher level in the

first half of 2016, prior to the Brexit vote.

UK imports from other EU countries and from China had

declined slightly during this period, but were continuing to

grow slowly from the main tropical suppliers including

Vietnam, Malaysia, Brazil and Indonesia (Chart 4).

The impact of Brexit on UK high street retailers in the

immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote seems to have been

muted. The British Retail Consortium (BRC) reports no

discernible impact on retail spending and shop prices

stemming from the EU vote. The first three months after

the referendum saw continuation of a two-year downward

trend in overall retail sales growth.

The one per cent year on year growth in the three months

to September was below the 1.2% average growth in the

twelve months leading up to the vote. Shop prices remain

firmly in deflationary territory, falling 1.8% year on year

in the three months following the vote.

The latest GDP data supports the general conclusion that

the economy has not yet suffered damage from the Brexit

vote, at least in the short term.

Data from the UK Office of National Statistics shows that

the economy grew by 0.5% in the three months to

September, slower than the 0.7% growth achieved in the

previous quarter but stronger than 0.4% growth in the first

quarter.

Annualised growth is currently at 2.3%, amongst the

highest of rich western economies this year. The IMF now

predicts that the UK will be the fastest growing of the G7

leading industrial countries in 2016.

However, the future implications of Brexit for the UK and

the wider EU market for wooden furniture remain very

uncertain.

Although some importers and retailers have been able to

protect themselves in the short term through smart

procurement and forward currency purchases, the pound*s

devaluation is likely to have dampened UK imports of

wooden furniture and other timber products over the

summer months and will continue to act as a drag in the

months ahead.

At some point in the near future, probably early in 2017, it

is widely expected that the pound*s devaluation will begin

to feed through into higher retail prices and slower sales.

Much press coverage on longer term impacts of Brexit

emphasises the downside, notably uncertainty created for

business investment and consumers, the potential for new

tariff and non-tariff barriers in trade with the UK, and the

possibility of rising labour costs if more stringent controls

are imposed on immigration.

None of this should be under-estimated, and politicians in

both the UK and EU face a considerable challenge to

reach an agreement that limits the economic and political

damage.

But expectations in the British retailing community (BRC)

are not entirely negative. This is well illustrated in the

speech by Richard Baker, the BRC Chairman, at an

October meeting of major UK retailers to discuss their

response to Brexit.

Baker was realistic about the challenges of greater

uncertainty, the weaker pound, and tighter controls on

immigration. He observed that a huge proportion of the

goods sold in the UK are sourced from outside the

country, with the EU being by far the single biggest part of

this trade.

There is no clarity at all on how much customs duty will

have to be paid on a huge range of items, both from within

and outside the EU, after Brexit.

However, Baker also noted that ※in my view there is good

reason to believe that smaller, more agile government that

is wholly focused on the needs of Britain has a good

chance of being more successful than one that must

endeavour to satisfy 28 member states and balance their

frequently conflicting agendas§.

Baker also wondered whether ※there is in fact potential for

reduced costs of trading§, speculating that there may well

be opportunities to reduce the burden on UK businesses

currently imposed by the EU through rules on competition

and state aid, environmental protection, workers* rights,

consumer protection and information, health and safety,

data protection, food and other product safety, and so on.

Under the terms of the Great Repeal Bill announced by the

UK Prime Minister in early October, the UK Government

plans to adopt EU legislation wholesale. However, once

the UK exits the EU, there will be a lengthy period of

national consultation when the UK government, guided by

the electorate, decides which rules to repeal, amend or

retain.

Baker indicated that during this period, the BRC ※will be

campaigning for an outcome that enables retailers to offer

great choice and value to their customers by ensuring

access to quality, responsibly-sourced, safe products from

all around the world, free of unnecessary costs and

charges§. Specifically, the BRC will aim to ※ensure that

there are no new tariffs and that the costs of bureaucracy

do not increase§.

Baker noted that that the UK retailer sector is the UK*s

biggest importer and pays billions of pounds each year in

customs duties. It therefore has a considerable stake in

ensuring a favourable outcome.

He noted that ※one BRC member has calculated that the

customs bill could quadruple without a trade deal with the

EU and if the UK loses its privileged trading status with

other countries. Any significant increase in tariffs will

inevitably find its way into shelf prices§.

On the other hand, according to Baker, there may be

opportunities to reduce tariffs where they currently exist.

There may be potential, for example ※for an extension to

the Generalised Scheme of Preferences to allow more

goods from developing countries to enter the UK free of

duty. This would be good for shoppers, good for retailers

and great for the UK*s commitment to a strong

international development agenda§.

It should be said that tariffs are not a particularly critical

issue for external suppliers of wooden furniture into the

EU. EU import tariffs are already zero on all wooden

furniture with the exception of components and kitchen

furniture which are subject to 2.7% tariff.

However, some suppliers of tropical wood would benefit

from a reduction of tariffs or extension of the GSP

framework by the UK. Tariffs of 4% to 5% currently apply

to planed, sanded and finger-jointed sawn tropical timber.

Hardwood veneers and plywood also attract tariffs of

between 3% and 10%.

Baker*s comments also show that UK businesses are not

just looking to minimise the damage from Brexit, or

waiting passively for politicians to come to terms, but are

looking creatively at the new opportunities that may arise

from Brexit.

If there is a so-called ※hard Brexit§ in which the UK fails

to reach agreement with the rest of the EU and withdraws

or is ejected from the single market 每 an event which

could occur as early as 2019 - there will be severe

economic fallout in the UK and, to some extent, other EU

countries.

But UK businesses would then have a very strong

incentive to expand trade with countries outside the EU.

This may be particularly significant for suppliers of

wooden furniture in the tropics whose main competitors in

the UK market are manufacturers located in the EU.

Impact of IKEA*s drive to expand market share

The continuing expansion of IKEA, the world*s largest

furniture company, is another factor driving change in the

EU market for wood furniture. In 2015, IKEA*s sales

increased by 11.2 % to euro 31.9 billion and the company

booked a net profit of euro 3.5 billion, 5.5% more than the

previous year.

Growth was well distributed across IKEA*s markets and

sales were highest in Germany, the US, France, the UK

and Italy.

At the end of the 2015 financial year, IKEA boasted 328

stores in 28 countries, 27 Trading Service Offices in 23

countries, 48 distribution centres in 17 countries, and 43

IKEA industry production units in 11 countries.

Much recent expansion has been in other regions, notably

in South Korea and India, but the company is still heavily

oriented towards Europe. Europe accounts for 229 Stores,

19 distribution centres, and 34 IKEA industry production

units.

Of IKEA*s purchases of home furnishing articles from

suppliers 每 both the company*s own industry production

units and external suppliers - 60% of value derives from

Europe, 35% from Asia, 3% from North America, 2%

from Russia and 1% from South America.

In terms of countries, China is now the largest single

supplier to IKEA, accounting for 25% of purchases,

followed by Poland (19%), Italy (8%), Sweden (5%) and

Lithuania (5%).

IKEA is the largest single buyer of wood material in

Europe, probably in the world. The company consumed

16.2 million cubic meters of wood (roundwood

equivalent) in the 2015 financial year, up 4% compared to

the previous year.

Around 60% of this comprised solid wood and 40% board

products. If paper and packaging is included, the company

is estimated to need close to 20 million cubic meters of

wood fibre every year.

Most of IKEA*s wood supply derives from Europe, the

largest suppliers being Poland (around a quarter),

Lithuania (7.5%), Russia (7%), and Sweden (6.5%).

Swedwood, an IKEA subsidiary, handles production of all

wood based furniture.

To date, IKEA has been almost entirely reliant on wood

owned and managed by other companies, but recently it

has bought a few relatively small forest areas in Romania

and the Baltic States in order to secure long-term access to

sustainably managed wood at affordable prices.

IKEA is not a major user of tropical wood and, in fact, has

played a leading role over the last quarter century to drive

European consumers towards the clean and light

&Scandinavian look*, heavily dependent on softwoods and

temperate hardwoods.

Due to the company*s very high profile, IKEA is

inevitably a principal target for negative environmental

campaigns whenever a tropical wood appears in any

product line.

One environmental group in Germany, went so far as to

test a wide range of IKEA products for tropical wood

content and launched a highly critical public campaign

following their identification of tropical wood fibre in

paper supplied by the company.

Nevertheless, IKEA has not excluded tropical wood from

their product range. The company*s Skogsta product line

is made of acacia which, in line with their broader

environmental strategy, seeks to maximise utilisation of

the material.

The product line shows off the natural colour variation in

the wood, utilising both the light blond and dark shades of

timber.

While IKEA does not exclude use of tropical wood in its

product lines, the company is ratcheting up the

procurement requirements imposed on all suppliers. Since

2000, IKEA has operated a supplier code of conduct for

purchasing all products, materials and services referred to

internally as IWAY. It sets out our minimum requirements

for suppliers, covering environment, social and working

conditions and it is a pre-condition for doing business with

the company.

Due to the volumes involved, IKEA*s timber procurement

policy has the power to drive wider changes in the wood

supply chain. In practice, IKEA have been a major factor

behind the moves to reduce the length of wooden furniture

supply chains, increase dependence of the European

wooden furniture sector on local wood supplies, and to

discourage a movement by manufacturers to other regions.

|