|

Europe

& North America

Identifying plantation forests in Europe proves difficult

The forest situation in Europe illustrates that there is often

no clear boundary line separating &plantations* from

&natural forest*. It is much more accurate to consider forest

ecosystems as a continuum with forests totally undisturbed

by man at one end and those totally dependent on man*s

intervention at the other. In Europe, the vast majority of

forest landscapes lie somewhere between these two

extremes.

According to a 2007 sustainability report issued by the

Ministerial Conference for Protection of Forests in Europe

(MCPFE), 87.2% of forest area in Europe (excluding the

Russian Federation) is classified as &semi-natural* forest 每

a category which includes a huge range of forest types

with different levels of naturalness and biodiversity. This

is inevitable in a region where man has interacted with

forests for thousands of years. Many forests that might be

considered &natural* by the local inhabitants 每 by virtue of

the fact that they contain mainly native species and are

extensively rather than intensively managed 每 may well

have been planted.

To overcome these difficulties of interpretation, MCPFE

defines plantations tightly as &Forest stands established by

planting or/and seeding in the process of afforestation or

reforestation which are either of introduced species (all

planted stands) or intensively managed stands of

indigenous species*. To be classified as a plantation,

MCFPE requires that the latter forest stands meet all the

following criteria: &one or two species at plantation; even

age class; and regular spacing*. MCPFE specifically

excludes &stands which were established as plantations but

which have been without intensive management for a

significant period of time*.

According to this tight definition, plantations cover only

about 16 million hectares, or 7.9% of the total forest area

in Europe excluding the Russian Federation. These

intensively managed tree crops are important for wood

production in several countries and form a very large share

of forest area in Ireland (85%), the UK (55%), and

Denmark (62%). Plantations also account for more than

10% of the forest area in Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal,

Belarus, Turkey, France and Albania.

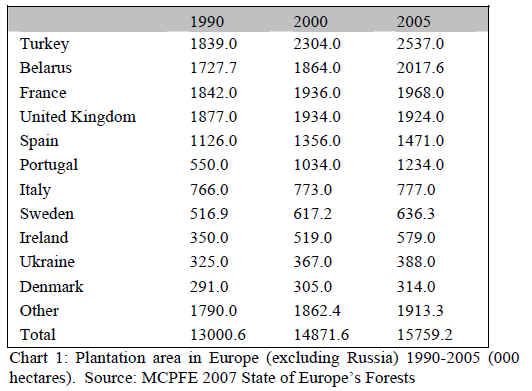

Plantation area in Europe (excluding Russia) increased by

2.8 million hectares in the period 1990 to 2005 at an

annual rate of 180,000 hectares. This was not at the

expense of either semi-natural or undisturbed forests, both

of which also increased during the 15 year period, by 8.0

million hectares and 1.2 million hectares respectively.

With regard to species, MCPFE collects data separately

for plantation area and for the area of forests dominated by

introduced tree species. Only a proportion of European

plantations comprise introduced species, while introduced

tree species also find their way into ※semi-natural§ forests.

However there is inevitably a close correlation between

the plantation data and the introduced species data.

MCPFE records that in total, about 8.1 million hectares, or

5.2% of the total forest area in Europe (excluding Russia)

is dominated by introduced tree species. The occurrence of

introduced species is highest in North West European

countries, where the proportion of forest area dominated

by introduced species is, on average, 15% of the total

forest area. Countries with the highest share of introduced

tree species are Ireland, Denmark, the UK, Hungary,

Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In the Baltic

countries, Finland, Switzerland, Slovenia, Belarus and

Serbia, introduced tree species have only been planted on

an experimental scale.

Typically, the number of introduced tree species for

forestry purposes varies between five and ten species in

Central, East and North West Europe. The most important

introduced conifer species for forestry purposes are:

Norway spruce (Picea abies), Sitka spruce (Picea

sitchensis), Douglas fir, (Pseudotsuga menziesii), various

pine species (most often Pinus contorta, Pinus nigra and

Pinus strobus), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and

larch species (Larix spp). Douglas fir is an important tree

species in several countries due to its fast and high wood

production capacity and excellent wood quality. Norway

spruce is often planted in Denmark, Belgium and the

Netherlands, where it does not occur naturally. Sitka

spruce is very common and an important introduced tree

species for wood production in the UK and Ireland. In

Sweden, the Contorta pine (Pinus contorta) has been

planted on over 0.5 million hectares. It should be noted

that among the important introduced conifers in Europe,

only Douglas fir, Sitka spruce and Contorta pine are

indigenous to territories outside Europe, specifically from

the western part of North America.

The most common broadleaved introduced tree species for

forestry and wood production purposes in Europe are Red

oak (Quercus rubra), false acacia (Robinia) (Robinia

pseudoacacia) and poplar species, especially Balsam

poplar (Populus trichocarpa x maximoviczil). Eucalyptus

species have been planted for forestry in Spain on over

200,000 hectares and in Portugal in about 700,000

hectares.

Plantation assets attract European and North

American investors

A key trend in the forest sector of North America and,

increasingly, in Europe in recent years has been growing

interest in timberland as a potential private sector

investment. Large amounts of money are being channelled

into forestry assets in two ways. First, large institutions

and wealthy individuals are investing in timber investment

management organizations (TIMOs). Such assets are

generally outside the reach of individual investors as they

usually require a minimum investment of several million

dollars. This has led to the emergence of a second

mechanism for ordinary investors seeking timber

exposure: specialized exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or

real estate investment trusts (REITs). REITs include Plum

Creek Timber, Rayonier, and Potlatch, all operating out of

the US. Examples of ETFs are the Claymore/Clear Global

Timber Index ETF and the iShares S&P Global Timber &

Forestry Index Fund ETF in the US, and the Phaunos

Timber Fund and Cambium in Europe.

The financial assets of these investment companies and

funds are now considerable and represent a major new

force in the global forestry industry. For example, the

Phaunos Fund alone had a Net Asset Value of USD495

million at the end of 2008, up from only USD115 million

at the end of 2006.

The US is still generally regarded within the financial

industry as the best place to invest in timberland, due to

the large areas of forest land available, strong forest

growth rates, a stable political system, clear and effective

systems of regulation and strong property rights. However

the recent influx of money is now chasing after a limited

number of forests in the country as American forestproduct

conglomerates have largely completed the process

of divesting millions of acres of forests to TIMOs and

REITs. As a result investors are increasingly looking

overseas for deals.

Nations wishing to attract these funds will need to take

effective measures to mitigate political, regulatory and tax

risks. Over time there is an expectation in the financial

community that institutional ownership of timberland by

large investment funds will become more prevalent on a

global basis.

An excellent series of articles on this trend has been

prepared by George Nichols, a researcher for a major

consulting firm, where he monitors market trends

regarding institutional ownership of alternative

investments. Nichols notes biological growth drives more

than 60% of total returns from timber assets, while timber

price changes and land appreciation account for the

remainder of returns. Timber investments have generally

outperformed stocks, bonds, and commodities over the

long run. In fact their performance has been exceptional.

Quoting data from Forest Investment Associates, he shows

that the North American NCREIF Timberland Index, the

standard benchmark for this asset class in the US,

increased 18.4% in 2007, versus a 5.5% rise for the S&P

500. Longer term, the Timberland Index has outpaced

major financial asset classes such as high-cap stocks,

corporate bonds and international equities. Timber returns

have been particularly high over the past couple of

decades.

Timberland assets are particularly valued because they can

improve a portfolio's risk-adjusted returns by virtue of

fairly low correlation to other asset classes. This low

correlation reflects the fact that the primary driver of

returns - biological growth - is unaffected by economic

cycles. Relative to the S&P 500, timber has exhibited low

downside risk. Since its 1987 inception, the NCREIF

Timberland Index has declined only in one year: -5.25% in

2001. By contrast, the S&P500 has fallen four times,

including -22.10% in 2002. Other benefits of timberland

assets are that they are a good hedge against long term

inflation and are often more tax efficient than other

portfolio diversifiers, generally being taxed at capital gains

rates rather than ordinary rates. Longer term prospects for

timberland assets seem particularly good now that

international policy-makers are developing systems to

increase financial incentives for forest carbon

sequestration.

But there are risks. In his article, Nichols suggests that the

physical risks to forests 每 for example from fire and

insects 每 are often over-stated, for example usually

eroding returns by no more than 0.1% annually for US

timberland holdings that are well-diversified by

geography, age, and species. Nichols believes more

significant risks are associated with illiquidity (the

inability to readily sell forest assets) and potential overvaluation

of existing timberland assets. The potential

benefits of investment in forestry-related assets are no

longer a &well kept* secret, and as more money chases a

limited number of viable forest assets, a bubble may

develop.

Nichols is also very critical of the way some REITs and

existing ETFs are portrayed as a surrogate for investment

in forests when in fact they are more closely linked to the

performance of the forest products industry, particularly

pulp and paper. However he suggests that this is not so

much a problem with some new funds recently launched in

Europe, some of which have significant assets in tropical

countries. These new funds generally share a commitment

to socially sound and sustainable forestry, often exhibited

through pursuit of FSC certification, as they seek to appeal

particularly to socially responsible investors.

One example is Cambium which trades on the Jersey

Islands Stock Exchange. Cambium sets out specifically to

&seek out opportunities to gain value from the certification

of its forest management systems, from the commercial

development of environmental products and services, and

from the reduction of risk by community engagement and

workforce development*. It notes that investments may be

managed for timber production, environmental credit

production or both, but that &the company will not engage

in processing facilities*. It is advised by New Forests Pty

Limited which aims to establish &a portfolio that comprises

geographically diverse assets located in mature and

developing markets as well as driving returns from

emerging environmental markets such as carbon,

biodiversity, and water quality*. Cambium*s total asset

value in April 2009 was around GBP102 million.

Investments include eucalyptus plantations in Brazil and

Australia.

Another example of this new breed of investment fund is

Phaunos Timber Fund Limited, launched in Dec. 2006,

which has made numerous investments in developing

countries, including in eucalyptus and teak plantations in

southern Brazil, eucalyptus plantations in Uruguay, and

various plantations in Tanzania, Mozambique and Uganda.

There is also Quadris Environmental Investment Fund,

which owns fast-growing teak plantations in Panama.

George Nichols articles on timberland investment funds

can be obtained at:

http://www.georgenichols.com/publishedwritings/timber/ti

mber1/index.htm.

The following is a good example of an article in the

mainstream business press 每 in this case Business Week -

about new funds allowing small investors to engage in

timber assets:

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/08_07/b

4071069413635.htm?campaign_id=rss_null

The following blog is a good critique of the claims made

for some of these funds:

http://thetimberlandblog.blogspot.com/2008/02/etf-assurrogate-

for-timberland.html

|