|

1.

CENTRAL/ WEST AFRICA

West and Central Africa show some progress on plantation investment

West and Central Africa have seen an upturn in plantation

investment in recent years, although attracting finance

initiatives in this region remains largely underdeveloped

compared to other tropical timber producer and consumer

regions. From an investor¡¯s perspective, the West and

Central African regions have higher risks, with less

possibility for quick returns from plantation growth. From

a government perspective, plantations are an attractive

investment, not only for reforestation initiatives, but also

for drawing benefits from emerging issues such as

reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation

(REDD).

With the exception of Ghana and Cote d¡¯ Ivoire, most

efforts in the Central and West African forest sector have

aimed to reduce log extraction and to certify forest areas.

There is regular harvesting of plantations in Cote d¡¯Ivoire;

however, the competition for export from low cost lumber

in South America has made the country¡¯s plantation

resources not financially viable at the present time. Nigeria

also has some extensive areas of plantation teak and a very

regular log export business, much of it reportly being

regular shipments for Indian buyers at prices that remain

very stable over long periods.

GHANA

Greening Ghana

Ghana was once one of Africa¡¯s largest timber exporting

countries south of the Sahara. However, illegal logging

has eliminated about 85% of the country¡¯s forest cover,

while forest fires have caused an estimated annual loss of

about three percent of the country¡¯s Gross Domestic

Product (GDP) during the last 15 years. Illegal logging

and wildfires particularly in the transitional and savannah

zones have been the most significant cause of

deforestation and forest degradation.

To address the continued deterioration of the forest, the

government has implemented various large scale

commercial plantation programmes throughout the

country. At various forums on forestation and

reforestation, Ghanaian private individuals, members of

academic institutions, civil servants and key forestry

stakeholder groups have been informed about forest policy

formulation, implementation and decision-making to

restore degraded forests in the country.

In 2001, the government officially launched the National

Forest Plantation Programme under the Forestry

Commission, in support of the government¡¯s massive

forest plantation initiative aimed at creating 20,000

hectares of degraded forest every year throughout the

country. To achieve this objective, the programme was

supported by the Forest Plantation Fund set up by the

government. The plantation programme was unique in that

it involved communities in almost every aspect, especially

the modified Taungya scheme, which offered 40% of the

proceeds to the participating rural farmers (see also TTMR

14:11). The modified ¡®taungya¡¯ system allowed degraded

forest reserves to be reforested with selected tree species

inter-cropped with food crops. Degraded forests have been

re-afforested annually with mixed species of cedrella,

emire, ofram, mahogany, teak and mangonia, all

endangered timber species. It is hoped efforts to restore

the forests would improve efficiency of the sector, protect

the forest resource to reduce the current shortage of raw

materials in the country and reduce poverty among rural

communities. It is also expected that about 80,000 new

jobs would be created annually at the community level.

The Minister of Lands and Natural Resources, Alhaji

Collins Dauda, launched this year¡¯s ¡®Greening Ghana

Day¡¯ at Yefri near Nkoranza North District in the Brong

Ahafo Region. Greening Ghana Day is an annual event

aimed at creating awareness about environmental issues

and also encouraging the public to embark on tree planting

initiatives, especially during the rainy season. The

initiatives have been well received by communities,

schools and various institutions. During this year¡¯s event,

the Minister made a passionate appeal to youth and key

institutions to engage in a massive tree planting exercise

throughout the country to help restore depleted and

degraded forest resources. It is estimated that if the

5,170,916 school children from primary and senior high

schools plant at least one tree per quarter per year under

the Greening Ghana programme, about 20,683,664 trees

would be planted every year.

In a recent development, the Minister of Lands and

Natural Resources has hinted it plans to promote the

development of plantations in the transitional zones of the

country to help boost agricultural production. Minister

Dauda announced commercial plantations would be

promoted in the country¡¯s transitional zones to help keep

the country¡¯s economy on track. He appealed to both

chiefs and land owners to support the government to

achieve its goal of making the country self-sufficient in its

raw material supply. The devastating effects of forest

degradation, especially during the past two decades, were

beginning to be seen in the deterioration of primary timber

species such as odum, mahogany, sapele and many others,

resulting in the drastic reduction in the raw material base

of the timber industry, a loss of biodiversity and the drying

up of water bodies including in tourist areas, all of which

are all important sources of national revenue.

Sunshine Technology to invest in plantation timber

According to OTAL, Sunshine Technology, a commercial

forestry plantation company, recently visited Ghanaian

officials to discuss possible investment opportunities in the

timber industry. A delegation from the company, led by

Sunshine¡¯s Chief Executive Officer, held a closed door

meeting with Ghana¡¯s President Mills. It is reported the

company is assessing sites in Ghana and Cote d¡¯Ivoire

covering approximately 50,000 hectares.

2.

SOUTHEAST ASIA

Plantations in Southeast Asia show dominance by oil palm

and rubber trees

Government officials in South East Asia have shown

strong commitment to plantation development mostly for

agricultural purposes. While there has been some

controversy over the growing of these species in Malaysia,

Indonesia and Myanmar, government and private sector

investment has continued to be focused on the

development of palm oil, rubber and acacia plantation

resources particularly in recent years.

MALAYSIA

Minister seeks to raise plantation productivity

The Malaysian Minister of Plantation Industries and

Commodities, Mr. Bernard Dompok, said Malaysia needs

to maximize major plantation crop yields. Oil palms,

rubber trees and cocoa trees accounting for the bulk of the

crops, which the Minister is seeking to raise yields without

expanding Malaysia¡¯s existing planted land area.

According to Bernama, he said the Ministry would

encourage ¡®better planting materials, good agricultural

practices (GAP) and enhanced research and development

(R&D)¡¯.

Currently, more than 70% of available agricultural land is

already planted with oil palms. The national crude palm

oil (CPO) yield stands at 4 tons per hectare annually.

However, some plantations are able to obtain a yield of 6

to 7 tons per ha. A study conducted by the Malaysian

standard organization, SIRIM Bhd, revealed that 2.65

million hectares of oil palm trees could yield up to 7

million tons of oil palm trunks and 26.2 million tons of oil

palm fronds annually. Oil palm fronds are a rich source of

fiber for the manufacture of MDF and other panel

products. The Minister continues to be hopeful that the

national CPO yield can be raised to 6 tons per hectare,

thus obviating the need to plant another 2 million hectares

of oil palms.

Rubber trees have historically been a popular plantation

species in Malaysia. The current yield of natural rubber

latex in Malaysia is 1.4 tons per hectare annually,

compared to Thailand, which has shown higher yields at

1.8 tons per hectare per annum. Currently, there are 1.24

million hectares of rubber trees in Malaysia. However, the

Malaysian Rubber Board (MRB) has launched the latest

high-yield clone, RRIM 3001, that could yield 2 tons of

natural rubber latex per hectare per year. The MRB is also

working on creating future rubber clones that could yield

at least 2.0 m³ of rubberwood per tree to meet the demands

of the Malaysian furniture industry.

For timber under the country¡¯s forest plantation

programme, the Ministry is looking to produce 75 million

m³ of timber by 2020 to meet the raw material

requirements of the Malaysian timber industry. Soft

commodities accounted for RM112.43 billion of the

country's exports in year 2008, or 17 % of Malaysia's total

exports.

INDONESIA

Report explores investments in plantations for raw

material supply to pulp and paper industry

Researchers recently analyzed and questioned the extent to

which Indonesian plantations are used in the Indonesian

pulp and paper industry. A working paper by Romain

Pirard (CERDI, France) and Christian Cossalter (CIFOR),

explored the resources of five major plantations across the

Indonesian island of Kalimantan, which are expected to

have a total standing volume of 1,013,707 m³ to 1,705,027

m³ of pulpwood in 2009 and 1,087,109 m³ to 2,063,189 m³

in 2010. The five plantations are associated with the

following companies: ITCI Hutani Manunggal; Surya

Hutani Jaya; Finnantara Intiga; Korintiga Hutani; and

Hutan Rindang Banua, which has remained a dormant

company. The following provides an overview of each

company¡¯s resources.

ITCI Hutani Manunggal¡¯s plantation consists mainly of

Acacia mangium. The concession also includes an

additional 3,000 hectares of sengon. At least 4,000

hectares of acacia planted are for the furniture market in

Surabaya. The yield of the concession is estimated at

about 80 air-dried tonnes (ADT) per hectare of pulpwood.

Surya Hutani Jaya was last known as a PT Arara Abadi

under the Sinar Mas group. Since 2004, the company has

harvested for 2,878 hectares of plantation harvested at an

average age of 6.7 years. The company had 49,000

hectares of very degraded natural forests in its concession

area. Acacia mangium was the main species planted and

Gmelina arborea was planted on a much smaller scale in

high pH soil areas.

For Finnantara Intiga, initially 157,000 hectares of a total

concession area of 299,000 hectares were not permitted to

be replanted or converted. Three species were planted by

the company for pulpwood. They are Acacia mangium,

(85% to 90% of the total area), Acacia crassicarpa and

Eucalyptus pellita.

The Korintiga Hutani nursery produced sufficient rooted

cuttings and seeds for a yearly planting programme of

7,000-8,000 hectares. Eucalypts may be planted on larger

areas in the future as their wood is considered better for

plywood and as mass production of clones seems to give

satisfactory results. However, Acacia mangium and

Eucalyptus pellita will remain the main species and are

harvested at an average age of seven years for pulpwood

production.

MYANMAR

Myanmar promotes plantation establishment

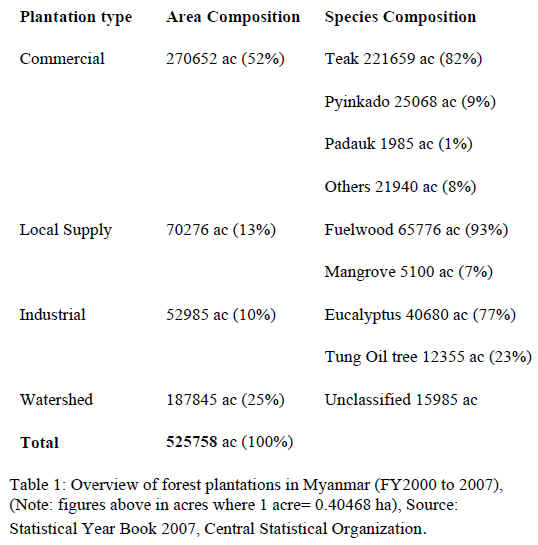

Plantations for commercial use, local supply, industrial use

and watershed management have been established in

Myanmar. Myanmar¡¯s Statistical Year Book (2007) shows

525,785 acres of plantations were established from 2000 to

2007. Plantation type, area composition and species

composition can be seen in the table below.

Plantations in Myanmar were established for various

objectives. Commercial plantations are mainly designated

for domestic timber supply and exports. Plantations

designated to supply the local market cover 70,276 acres

(28,440 ha) for fuel wood, posts and poles. Industrial typeplantations

of 52,985 acres (21,442 ha) are for paper mill

supply. Plantations for watershed management (catchment

protection) cover 187,845 acres (53,356 ha) to prevent

erosion. Teak accounts for the largest plantation area of

221,659 acres (89,702 ha). The objective of these

plantations is to help increase production while reducing

pressure on natural forests.

Establishing systematic teak plantations began in 1856

using the Taungya method, an afforestation method where

crops are interspersed with trees on cleared land.

However, the extent of plantations at that time was very

limited to small scale compensatory plantings to enrich

and supplement the growing stock. The post-World War II

population boom resulted in an increased use of timber

products. Changes in land-use patterns and the

deterioration of natural forests further exacerbated

pressure on forests. To address the situation, plantations

were established to expand the modest compensatory

plantings into large scale block plantations since 1962.

From 1896, plantation establishments were systematically

organized by the Forest Department (FD). Since 1984, FD

had been establishing 30,000 hectares of plantations

annually. The total teak plantation area from 1896 to 2007

was 384,123 hectares. Other species planted during the

same period were: pyinkado (61,899 hectares); padauk

(17,426 hectares); pine (21,685 hectares); and others

(421,376 hectares). The teak plantation area is about 18%

of the global teak plantation resources.

It is not clear how much plantation timber has been

harvested and traded in Myanmar. Most people from the

timber trade tend to connect plantations with natural

forests. This perception is due to the observation that teak

and other valuable species are planted to compensate for

the natural forests. Sales of poles and posts are the only

way to trace teak from plantations in the timber trade. In

other cases, it is necessary to devise a statistical system by

respective departments to differentiate which trees are

from plantations and which are from natural forests.

The Ministry of Forestry formulated a Special Teak

Plantation Programme (STPP) in 1988, designed to

establish 8,100 hectares of plantations every year for 40

years, with a view to creating 324,000 hectares of teak

plantations. The Forest Department estimated that, after

the year 2038, annual sustainable teak production could be

as high as 1.8 million m³.

In the past, establishment of teak plantations and

harvesting of teak has been conducted solely by the State.

According to Myanmar Forest Law of 1992, ¡®A standing

teak tree wherever situated in the State is owned by the

State¡¯. However, in 2005, the Myanmar government

granted permission to local investors to establish teak

plantations. This has been a great opportunity for local

entrepreneurs. Under this scheme, the government leases

forest land to local investors to plant teak. The investment

returns from teak plantations are shared between the

government and the investor on a 20:80 basis. Increasing

demand for teakwood, coupled with technical advances in

processing led to greater participation from the private

sector in establishing plantations. It is reported that many

private investors are now involved in plantation

investment in Myanmar.

There are also a number of challenges facing investors in

the country. Long-term investments require proper

planning, appropriate agro-forestry practices mixed with

short-term tree planting. To combat illegal activities, law

enforcement, patrolling and income generation in the

community is required. To reduce the monoculture effect,

a buffer zone in the plantation area needs to be established

and mixed species need to be planted. It is suggested that

investors should proceed with caution before investing in

teak plantations, as improvement of teak quality and

maintenance and further research on utilization of small

diameter logs is required.

3.

SOUTH

ASIA

INDIA

Plantation areas expand in India

During the ¡®Van Mahotsav Festival¡¯ or ¡®Festival of

Forests¡¯, a large number of trees are planted in every state

of the country. The forest department also helps local

communities and village-level panchayats to plant millions

of saplings, which are mostly distributed free of cost. For

planting in urban areas, the saplings are distributed at

nominal charge of about Rp. 1 per sapling (TTMR 13:15).

In conjunction with the event, the Karnataka Forest

Department decided to promote sandalwood cultivation in

the district of Chitradurg by distributing 50,000 saplings of

sandalwood. This was achieved as a result of an

amendment to the Karnataka Forest Rules of 1969,

enabling certain norms relating to sandalwood cultivation

by private parties to be changed. Previously, those

cultivating sandalwood saplings had to sell harvested trees

only to the state forest department, thus reducing the

incentive for people to cultivate sandalwood. The

amendment allows the sale of sandalwood directly to

semi-government agencies, making it much easier and

faster to sell products in the market. To avoid smuggling

and illegal trade, the department is involved in the sale of

the wood and keeps records of timber sold. The

government is generating incentives for farmers to

cultivate this species by offering a 75% subsidy to

establish these plantations. Similar programmes are being

carried out in other districts of Karnataka.

The establishment of plantations in India has had a mixed

history. In 1956, the price of sandalwood was Rs.6 per kilo

compared to the current value of up to Rs.6000+ per kilo.

Based on the guidelines of the present government¡¯s

import-export policy, sandalwood logs can only be

imported under license. This is a big deterrent for

sandalwood-based factories from getting raw materials

and for thousands of handicraft workers who depend on

income from sandalwood carvings. The present restriction

on imports of this timber has created scarcity of raw

material for the artisans. This shortage also encourages

smuggling of sandalwood trees from government as well

as private entities. All timber imports in India with the

exception of sandalwood are under the Open General

License (OGL), meaning these are sold without tax.

Imports of sandalwood logs could be stimulated if these

could be designated as eligible for OGL to bring down

prices and stop illegal smuggling of the species. Given the

current shortage of raw materials (if corrective measures

are not taken), many experts believe the handicraft

business will vanish.

One socio-religious institution, BAPS, has taken a bold

decision to plant 100,000 saplings of Santalum album in

the land attached to their temples and have already made

strides to undertake planting activities. In India, temples

have a large use for sandalwood and the newly planted

trees are expected to help meet these needs. Captive

plantations by companies manufacturing mouth freshener

¨C pan masalas ¨Chave also been established in Madhya

Pradesh in and around Katni where over 200,000 saplings

have been planted.

Santalum album has been planted in North Gujarat around

Mehsana, South Gujarat around Valsad and in coastal

areas of South Saurashtra. These areas are not natural

areas for sandalwood. Experimental plantings are under

study, although some eucalypt plantations in experimental

areas have already shown success in the State of Gujarat.

The state government and its Forest Department are fully

supportive of encouraging plantations to boost local

incomes, supply raw materials to wood working units and

provide poles to the building industry.

On the contribution of plantations to combating climate

change, DNA India says that the State of Haryana is

committed to combat climate change and ¡®green¡¯ Haryana.

The Chief Minister has announced a policy to promote

forest cover in the state. The present tree cover in Haryana

is 7.13%, and is envisaged to increase to 10% by 2010 and

20% by 2020. Apart from government efforts, other

private entities are also establishing plantations of

eucalypt, poplar and acacia to supply raw materials. Those

establishing plantations also receive assistance and the

state government has pre-identified 800 villages in the

state for afforestation and poverty alleviation activities.

Innovative initiatives in agro-forestry have been

introduced for the benefit of small and marginal farmers

while augmenting the supply of raw materials to the woodbased

industries in the state.

Similarly, companies in other states also keep establishing

timber plantations to meet their requirements for raw

materials. ITC Ltd has by now almost 100,000 hectares of

eucalypts, casuarinas and subabul in Andhra Pradesh for

making paper pulp. Mangalam Timber Ltd, an old player

in MDF manufacturing has initiated forestry activities as

early as 2001 and has now some 50,000 acres under

eucalypts in Orissa, Chhatisgarh and Andhra Pradesh. The

emphasis is to be independent and to ensure steady supply

of logs for MDF production. Many businesses are

establishing plantations in order to be self sufficient in

their raw material supply and to stimulate measures to

combat climate change.

Reliance Industries also have approximately 7,500 acres of

mango and teak plantations to improve the environment

around their refineries near Jamnagar. Plywood factories

in Haryana and Uttaranchal draw most of their

requirements from poplar and eucalypt agro-forestry

crops. A particleboard manufacturing plant of 300,000 m³

per year capacity is being established by the Associate

Lumber group owned by the Agicha and Darvesh families

in the State of Karnataka. The group is also planning to

establish 25,000 hectares of plantations to meet their raw

material requirements.

There have been many tree planting activities along

canals, railway tracks, highways and the harvest from

these plantings have significantly augmented timber

supplies in the country. The antique furniture reproduction

units in Rajasthan are getting most of their supplies from

Canal bank Sissoo (Dalbergia sissoo) plants. Acacia

mangium and Melia dubia plantations in Kerala and

Karnataka are providing good timber for doors, windows

and building joinery components. Bamboo and eucalyptus

are meant for the paper and rayon pulp industry. Kerala

has the largest share of teak plantations. Maharashtra,

Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat Orissa and other states also keep

expanding teak plantations and the harvested logs are sent

to government forest depots for auction.

Since India has yet to reach its forest cover of 33% of the

land area, state governments do not cut trees in natural

forests. India¡¯s demand for teak is much more than what is

available presently - it permits imports of teak and other

timber freely without any license or permit requirements.

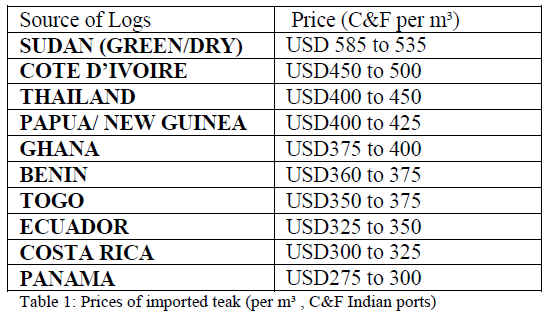

Below are countries which export teak to India (from

sources other than Myanmar) at current C&F prices for

Indian ports.

Measurement systems for plantation teak are different,

depending on the exporting country. Some countries allow

a 10 cm deduction in girth to compensate for bark and

sapwood, while others allow 6 cm or only 2 cm.

Therefore, if the importers are not well versed in the

matter, they suffer. Teaknet plans to take up the matter of

uniform specifications, measurement systems and

allowances for sapwood and bark and some guidelines on

uniform price vis-¨¤-vis classifications. The local practice

in India is for the logs to be measured under the sap,

whether it is teak or another timber. To protect buyers and

consumers, the ideal system would be to measure logs

under the sap so allowances for sapwood and bark will not

arise. It is hoped that Teaknet will take up this matter in

due course, possibly at the international seminar planned

by them during the month of November 2009 (see TTMR

14:13).

4.

LATIN

AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN

Brazil benefits from greatest investor interest in

plantations

Much investment in plantations has been centered on Latin

America, given its attractive investment environment.

Brazil, Peru, Mexico and Guyana have all experienced

growth in their plantation areas in the last few years. In

particular, institutional and individual investors are drawn

to Brazil, as it has shown promise in generating attractive

returns for investors¡¯ portfolios.

BRAZIL

Eucalypts and pine dominate plantations in Brazil

Forest plantations play a fundamental role in the socioeconomic

development of the country, contributing to the

production of goods and services, adding value to forest

products and generating jobs, foreign exchange, taxes, and

income. Yet, it is estimated that forest plantations account

for about only 1.5% of the existing forests in Brazil,

although they play a major role in forest products markets

accounting for an estimated 70% of the total industrial

roundwood production.

Total plantations in the country are estimated at 6,582,700

hectares in 2008, about 93% of which comprises eucalypt

and pines, with the remaining 7% from other species

(notably wattle, rubber tree, paric¨¢, teak, Parana pine and

poplar).

The main planted species in Brazil are mainly investments

for profit; afforestation and reforestation programmes of

forest companies are geared to supply industrial

roundwood for the well-established and diversified forest

products industry of the country (e.g., pulp and paper, pine

lumber/sawnwood, reconstituted wood panels, pig-iron

and steel industry, and energy wood).

Such plantations are oriented to supply the industrial

roundwood needs in the country, for both the domestic and

export markets. The high productivity of plantations,

relatively low production costs, extensive land area and

advanced technology in Brazil gives the country

comparative and competitive advantages in establishing

plantation forests, making it an important producer of fastgrowing

plantation forest products.

While plantation sites set aside for pine and eucalypts

range from those in degraded areas to those for agriculture

purposes, the plantations are generally geared for

production of industrial roundwood. It is worth

mentioning that the growing importance of partnership

forest plantation programmes between large corporations

and small to medium-size landowners in the last few

years.

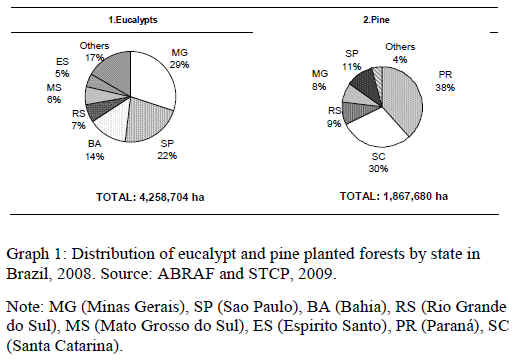

Forest plantations with eucalypts and pine were estimated

at 6,126,000 hectares in 2008. Eucalypts accounted for

4,259,000 hectares, while pines accounted for 1,867,000

hectares. Graph 1 below shows the distribution of eucalypt

and pine planted forest in the main Brazilian states.

A total of 1,439,276 ha of planted pines in Brazil in 2008

(77%) are concentrated in the South (states of RS, SC and

PR). The Southeast region comprises 56% of eucalypt

planted area in the country (ES, SP and MG). Minas

Gerais has the largest combined eucalypt and pine planted

area in Brazil (1,423,212 ha), followed by São Paulo

(1,142,199 ha).

The largest Brazilian companies establishing forest

plantations are associated to the ABRAF (Brazilian

Association of Forest Plantation Producers). These

companies together account for 55% of the total planted

area in the country. As for planted forests by industrial

segment among ABRAF members, the largest area

belongs to companies in the pulp and paper segment (76%

pine and 70% eucalypt). As for pine, the segments of

reconstituted panels and iron and steel industry

concentrate, respectively, account for 15% and 9% of the

planted area. On the other hand, for eucalypts, 21% of the

area belongs to the iron and steel industry, and 6% to

reconstituted panel companies among ABRAF members.

Most companies of the forest sector were affected by the

global economic crisis since the last quarter of 2008. As

future investments in the planted forest sector depend on

the recovery of the economy, investments in forest

plantations for the next few years are expected to be

reduced with planting in 2009 being possibly the most

affected.

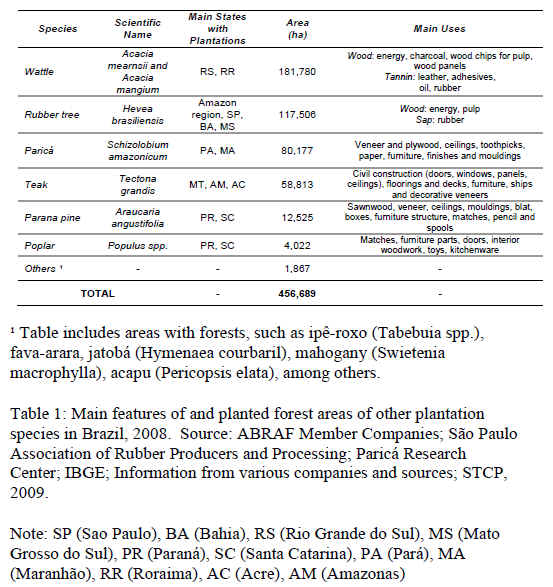

Although eucalypts and pine are the dominant planted

species in Brazil, other species such as acacia/wattle,

rubber trees, paric¨¢ and teak account for a significant part

of the so-called other species. They also deserve attention

due to their economic importance and recent expansion of

their plantation area. Table 1 presents forest plantations

areas and relevant aspects of other species planted in

Brazil.

Acacia/Wattle plantations in Brazil (Acacia mearnsii and

Acacia mangium) are concentrated in Rio Grande do Sul

(South) and Roraima (North). In Rio Grande do Sul, A.

mearnsii (black wattle) is cultivated by thousands of small

forest producers, which supply companies of the tannin

segment (extracted from acacia bark). Acacia production

is designed to meet both foreign and domestic demand,

with consequent job and income generation in Brazil.

Black wattle wood is used as fuelwood, for charcoal

production and exported as wood chips for pulp, mainly to

Japan. The tannin destined for the domestic market and

supplies the tannery, adhesives, oil, and rubber sectors,

among others. In addition, part of Brazil¡¯s tannin

production is exported to over 50 countries.

The rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) is cultivated for

rubber latex tapping for the production of natural rubber,

while the rubber wood can be used for fuelwood or for

furniture production. The species is originally found in the

Brazilian Amazon, but is planted in Northern states. Minas

Gerais has natural conditions (soil, climate, topography

and water availability) and favorable geographical

locations to expand rubber tree plantations on a large-scale

for agribusiness activities, according to EPAMIG

(Agricultural and Livestock Research Institute of Minas

Gerais). Thus, it is expected that rubber tree plantations

would increase steadily in the state. Such competitive

advantage has been explored for many years by states such

as São Paulo, Mato Grosso, Bahia and Mato Grosso do

Sul. EPAMIG (Corporation for Agricultural and Livestock

Research of Minas Gerais) has undertaken studies based

on the Brazilian strategy to avoid dependence on imported

natural rubber, used as a raw material for various products.

Paric¨¢ (Schizolobium amazonicum) plantations are

concentrated in the Northern states of Par¨¢ and Maranhão.

This species is native to the Brazilian Amazon and is

suitable for manufacturing veneer, plywood, ceiling,

toothpicks, furniture, wood finishing, and mouldings.

Teak (Tectona grandis) plantations in Brazil are located

mainly in Mato Grosso, Amazonas and Acre. It is

considered one of the most valued timbers in the

international market, which is the reason for its expansion

in plantation areas in recent years. Its main uses are for

civil construction (doors, windows, panels, ceilings, etc.),

flooring and decks, furniture, shipbuilding (roofs, flooring,

ceilings), decorative veneer, decoration and ornaments in

general (sculpture and woodcarving). Teak was planted

about 25-30 years ago in Brazil (with an area by that time

quite small compared to the total current plantation of

nearly 60,000 hectares ¨C mainly in Mato Grosso). Thus,

most plantations are still at a young age (not yet

managed/thinned). Plantations are concentrated among 10

major companies and only few of them have mature

forests producing high-value timber products for export.

The remaining companies are about to start managing their

young plantations (thinning at a low age of 8) and will

therefore be producing small-diameter logs for low-end

domestic product markets (fuelwood/residues).

Parana Pine/Araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia) forest

plantations are located mainly in the Southern states of

Paran¨¢ and Santa Catarina. The main wood utilization is

for sawnwood and veneer, solid wood products, such as

ceilings and mouldings, furniture, long-fiber pulp, among

others. Despite its importance for certain regions,

araucaria planted area in Brazil decreased over the last few

years. This is mainly due to its substitution by other fastgrowing

species and laws restricting araucaria logging

(including natural and planted forest). In addition, the

IBAMA Administrative Ordinance (Instrução Normativa)

06/08 lists araucaria as a threatened native species;

therefore, it is subject to legal restrictions on its

harvesting, for any purposes, which can be done through a

permit obtained from the competent environmental

agency.

Poplar (Populus spp) forest plantations are also

concentrated in Parana and Santa Catarina. This is a minor

planted species, generally used in manufacturing of

matches, furniture parts, doors, interior woodwork, and

others.

Investors diversify portfolios with Brazilian plantations

Brazil has attracted significant direct investments in recent

years. Such investments are a result of from the high

competitiveness reached by the country in plantation

forests. Brazil has integrated its competitive advantages in

the forest sector through favorable natural conditions,

scientific knowledge and entrepreneurial capacity, which

results in a highly competitive potential growth.

Brazil ranks first in the Inter-American Development Bank

(IDB) Forest Investment Attractiveness Index (IAIF) for

the Americas. Such index measures the attractiveness of

the forest sector of Latin American & the Caribbean

(LAC) countries for direct investment to guide investors in

selecting countries with high potential for successful

investments in the forest sector. Brazil leads with a score

of 60 out of 100. It is followed by Chile, Uruguay and

Argentina. Investors associated with forest investment

have established and acquired forest assets, pointing to a

continuous growth of Brazilian forest plantations.

The instruments with high growth in the country are

investment funds in forest assets for pension funds and

forest funds specifically established for this purpose.

These funds have different sources, including domestic

and foreign capital, and many other funds are still in the

process of development, and are geared primarily to the

establishment of fast-growing forests (planted forests) not

necessarily linked to industrial projects.

Investment funds can be managed by TIMOs (Timberland

Investment Management Organizations) or by companies

specialized in forest management. TIMOs have been a

way of organizing successful investors in Brazil, mainly in

the Southern region, with planted pine forests. In some

cases, TIMOs themselves have capital for investment in

forests. Despite the global economic crisis, experts suggest

TIMOs work will increase in Brazil in the coming years.

To purchase forests in Brazil and elsewhere, investment

funds concentrate mostly on the acquisition of mature

forests, which may include afforestation, buyback

guarantee for timber, price setting and other mechanisms.

However, there are variations in investment types and

forms. In Brazil, due to the limited availability of forest

assets, investment funds have been more diversified, with

some focusing on niche markets of less value-added

products such as pulpwood and charcoal.

Brazil has great competitive advantages for production

forests compared to other countries such as high

productivity in species such as eucalyptus (average of 35

m³ of wood/ha) and short rotation cycles of 6-7 years for a

first harvesting. The volume of CO2 sequestered by a

forest depends on the species planted, clone type, soil and

climate conditions, forest management and others. It is

estimated that a eucalypt forest with such average

productivity contributes to the sequestration of

approximately 200 ton of CO2 equivalent per hectare per

year.

As an alternative to the scenario set by the Clean

Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto

Protocol, Brazilian forestry companies concentrated their

efforts on climate change for the Chicago Climate

Exchange, where more flexible rules allowed carbon credit

generation and trading for forest projects in eligible under

the current CDM rules. As a new undertaking, a number of

companies have studied opportunities for the

establishment of afforestation/reforestation and REDD

projects associated with the carbon credit markets. Such

projects are yet to be developed in the country.

Future outlook for plantation species in Brazil

In 2008, Brazil was upgraded from speculative grade to

investment grade in the credit ratings index of Standard &

Poors, which allows a country to capture external capital

resources at lower interest rates (low risk premium of debt

securities).

Besides this rating, Brazil offers attractive factors for

foreign investors, including the possibility of access to a

broad and growing consumer market and greater political

stability. Given the current international economic crisis, a

shortage of external credit and low investment, Brazil has

become an alternative to business groups that have greater

liquidity and are ready to invest. The comparative and

competitive advantages of the country in the forest sector,

especially with fast-growing plantations, almost

guarantees high returns to investors.

In Brazil, the forest sector has developed mainly based on

domestic direct investments. However, foreign direct

investments flows have also increased in recent years. In

the short-term, the global financial crisis may only delay

the previously announced investment plans in the forest

sector; on the other hand, in the medium and long-term,

the implementation of mega-investments is expected in

planted forests and the forest-based industry. This

perspective promises to increase production, in both

forests and industrial processing, to levels never

experienced in the past.

Investments in planted forests in traditional forest

plantation states and in new forest frontiers represent a

new phase of the planted forest sector¡¯s growth, to

generate jobs and income, product diversification, social

inclusion, and foreign exchange earnings for the states

benefited with large-scale forest plantations.

The investment prospects (2009/2012) for the pulp and

paper industry, based on a BNDES survey carried out in

August 2008, was around BRL26.7 billion. This estimate

has been reduced drastically to BRL9.0 billion in

December 2008. This shows a significant decrease of 66%

in the investment prospects of the Brazilian pulp and paper

industry. According to the BNDES study, this reevaluation

is due to the lack of confirmation of

investments and postponements of projects rather than

cancellation.

The forest sector (mostly the plantation sector) currently

generates more than 700 thousand direct jobs in Brazil.

STCP consulting estimates that in 2030, the sector will be

able to generate 1.6 million direct jobs, with one-third in

the silviculture (plantation) area. This estimate shows the

sector will be among the three biggest job generators in

Brazil in the coming decades.

Recent estimates for the next decade have recognized the

need to expand forest plantations from the current 6-7

million hectares to nearly 20 million hectares by the year

2050. This is to supply the growing demand for industrial

roundwood of the highly-diversified and expanding forest

products industry in the country and new direct

investments expected by domestic and foreign investors.

PERU

Forest plantations in Peru show potential for growth

In Peru, the government invests a small amount of funds to

implement reforestation or afforestation projects for

industrial or commercial purposes. The reforested land for

commercial purposes has been established by means of

private investment. Experts note that little investment

exists from the Peruvian government, even though

products consumed by Peruvians are derived from wood

from neighboring countries. They have indicated a number

of problems with plantation forests in Peru including lack

of finance and capacity, weak institutions and

underdeveloped markets for products. Technological

innovation has not spread to the forest sector and many

regions continue working with outdated technologies to

harvest and process wood.

Nevertheless, according to the INRENA, there exists a

great potential to develop plantation areas. The Fund to

Promote Forest Development (Fondebosque), a

government institution, is using two mechanisms to

finance diverse projects in the Peruvian Amazon. The first

mechanism is a fund that has finances business plans up to

USD18,000 for machinery, equipment and tools through a

short-term bank credit. The beneficiary uses the machinery

and later pays back the credit in monthly installments. A

second mechanism involves partial grant by

FONDEBOSQUE and partial contribution from the

beneficiary. It provides finance for associations,

cooperatives and producers¡¯ networks up to USD65,000

for civil works, machinery, equipment, tools, inputs and

training activities. Sound business plans are required to

access both funds to demonstrate the technical, economic,

environmental and social viability of the plan.

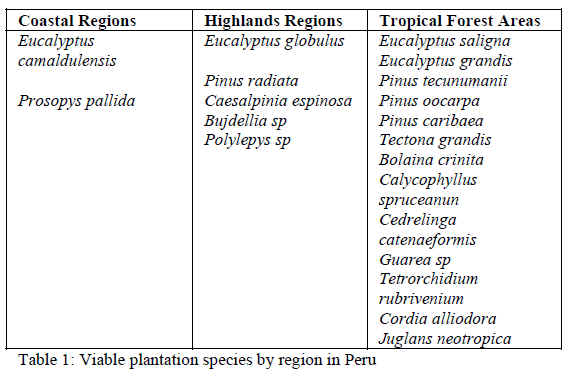

A number of geographical areas in Peru also have a great

potential to be developed with plantations. In particular,

the following are areas where plantations could be

established: the Department of Pasco in Oxapampa; the

Department of Junin in the Valley of the Mantaro, Satipo;

the Department of San Martin in Tocahe, Tarapoto; the

Department of Ucayali in Coronel Portillo; and the

Department of Huanuco in the Code of the Pozuzo. The

table below shows the type of plantation species that can

be planted in Peru by regional ecosystem:

MEXICO

PRODEPLAN sets pace for forest plantation development

The programme for the development of commercial forest

plantations (PRODEPLAN) will be implemented in 32

states of the country and given special attention to targeted

populations. The beneficiaries of the programme can be

individuals or entities and are selected by a committee

following the terms and conditions established in the

Rules of Operation and Assembly, which are issued by the

National Forest Agency CONAFOR. As part of the

development of commercial plantation programmes,

ProTree also has different programmes for this purpose,

which include the programme for the establishment and

maintenance of commercial forest plantations. As part of

the programme, the following plantations will be

established: non-timber plantations of both arid and

tropical species; plantations of Jatropha curcas; agroforestry

plantations with timber species; and Christmas

tree plantations.

The government is also granting financial support for the

management, technical assistance and insurance of

commercial forest plantations. The federal budget for

supporting such programmes amounts to a total of

531,697,791 Mexican pesos. Of the total, 88% is dedicated

to support the establishment and maintenance of

commercial forest plantations, which is up 2.5% this year

for operating expenses and project evaluation and nearly

10% for project supervision. The maximum amount of

support to be granted for the establishment and

maintenance of commercial forest plantations and

developing management programs will depend on the

maximum limits for each type of plantation included in the

Rules of Operation.

To have access to ProTree resources, individuals should be

Mexican nationals or entities incorporated under Mexican

law to participate in the general selection procedure. The

Rules of Operation for Commercial Forest Plantations

state that eligible parties: are owners or holders of land,

preferably of forest or temporary forest land; should

provide a description of projects, preferably for forest land

or temporary forest land; submit their applications and

respective proposals in line within the appropriate

deadlines, terms and conditions established in the

Assembly and in accordance with these Rules; are not

subject to any other support or subsidy from the Federal

Government such as replacement from or overlap with the

ProTree program in this category, based on the opinion

given by the General Coordinator of Production and

Productivity of CONAFOR.

Domestic and foreign companies established under

Mexican law have excellent investment prospects from

commercial plantations in the country. Mexico has 11

million hectares dedicated to forestry activities, although

the area also has some agricultural uses with lowproduction

farms. With further capacity building, private

investment and federal support, it is anticipated that

sustainable and productive commercial forest plantations

can be developed.

Investment returns for commercial forest plantations in

Mexico is less than in other countries in the region.

Nevertheless, there is a diverse set of ecosystems in

Mexico where: a number of trees are being planted in

temperate, cold and warm/wet climates; access to land is

relatively simple and there is infrastructure available; they

are also strategically located in relation to high

consumption areas - North America, the Pacific Rim and

Europe. Moreover, the federal government provides

economic support incentives in forest plantations, in

addition the average rate of return on investment or

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) obtained in Mexico is higher

than that achieved in similar projects in other countries.

Domestic or foreign investors can invest in new projects,

from the beginning or engage in projects that have already

commenced, and in some cases beyond the stage next to

pre production. To become involved in an on-going

project, experts suggest establishing a relationship with a

Mexican company or joint venture (domestic and foreign),

which already has plantations but requires an injection of

capital to expand its planted area. There are also a large

number of afforestation or commercial forest plantations

that are in a pre-productive phase and require partners with

new financial resources even though they already have

financial support from the federal government.

A second strategy is to start a new plantation project

through a subsidiary company, incorporated under

Mexican law, which could directly be involved in

operational activities such as feasibility studies for

projects, assessments of locations for new projects,

selection of plantation species, programme management

and presentations to SEMARNAT, plantation

establishment and protection and management of

plantations.

The investor that is engaged in a joint venture with a

Mexican company or prefers starting on his/her own can

access the support offered by the Mexican government. It

is noteworthy that, whether or not he is beneficiary of

federal funding, any investor in Mexico has the legal

protection of the Mexican law, as long as the contracts

associated with the rental, purchase, rural partnership or

joint venture for the project are registered with the

Secretary of Agrarian Reform. If foreign investors engage

in commercial forest plantation projects, they must comply

with Mexico¡¯s Foreign Investment Law.

For more information on plantation investment in Mexico,

contact Carmelo Hermandez, Manager for Development of

Commercial Plantations at 52-33-37-77-70-00 Ext. 2200

to 2223 or Toll Free 1-800-50-59-888 or email

chernandezp@conafor.gob.mx.

GUYANA

Plantations have long history in Guyana

After the Second World War, colonizers set up a number

of pilot plantations as permanent research plots to

investigate the growth rate of Pinus Caribaea under

different treatments ¨C soil types, pruning and fertilizer.

Pinus Caribaea were planted at Bartica from 1955-1965

and Ebini from 1964-1968.

Steadily rising prices for lumber coupled with more

recognition of the (non-timber) values of natural forests

seem destined to drive forest enterprises into the

establishment of plantations. The Guyana Forestry

Commission (GFC) has demonstrated in the past that

exotic species such as teak (Tectona grandis) and

Caribbean pine (Pinus spp.) can grow commercially in

Guyana. It has been observed too that various local species

such as tauroniro (Humiria balsamifera), and simarupa

(Quassia simarouba) have potential as plantation species

because they require a high amount of light and grow well

on poor sandy soils.

There are many areas in Guyana which could benefit from

plantations, especially the large expanses of savannah

lands located in the hinterland areas of Guyana.

Communities can certainly benefit economically from

managing nurseries and producing seedlings for sale to

persons engaged in setting up plantations. Nursery

practices (and seed technology) could also provide

employment for women and the aged.

Silvicultural projects based on plantations carry two major

challenges. The first is to choose the right species (light

demanding, fast growing, robust in the face of poor soils,

pests and water scarcity). The second challenge is the cost

of inputs and tending activities, once the trees start to

grow.

The revised Forest Act also recognizes the value that

plantation forests can bring to Guyana by encouraging the

establishment of same. The GFC and other institutions,

such as the University of Guyana, and the Guyana

Geology and Mines Commission have already initiated

discussions on promoting this as an activity.

|